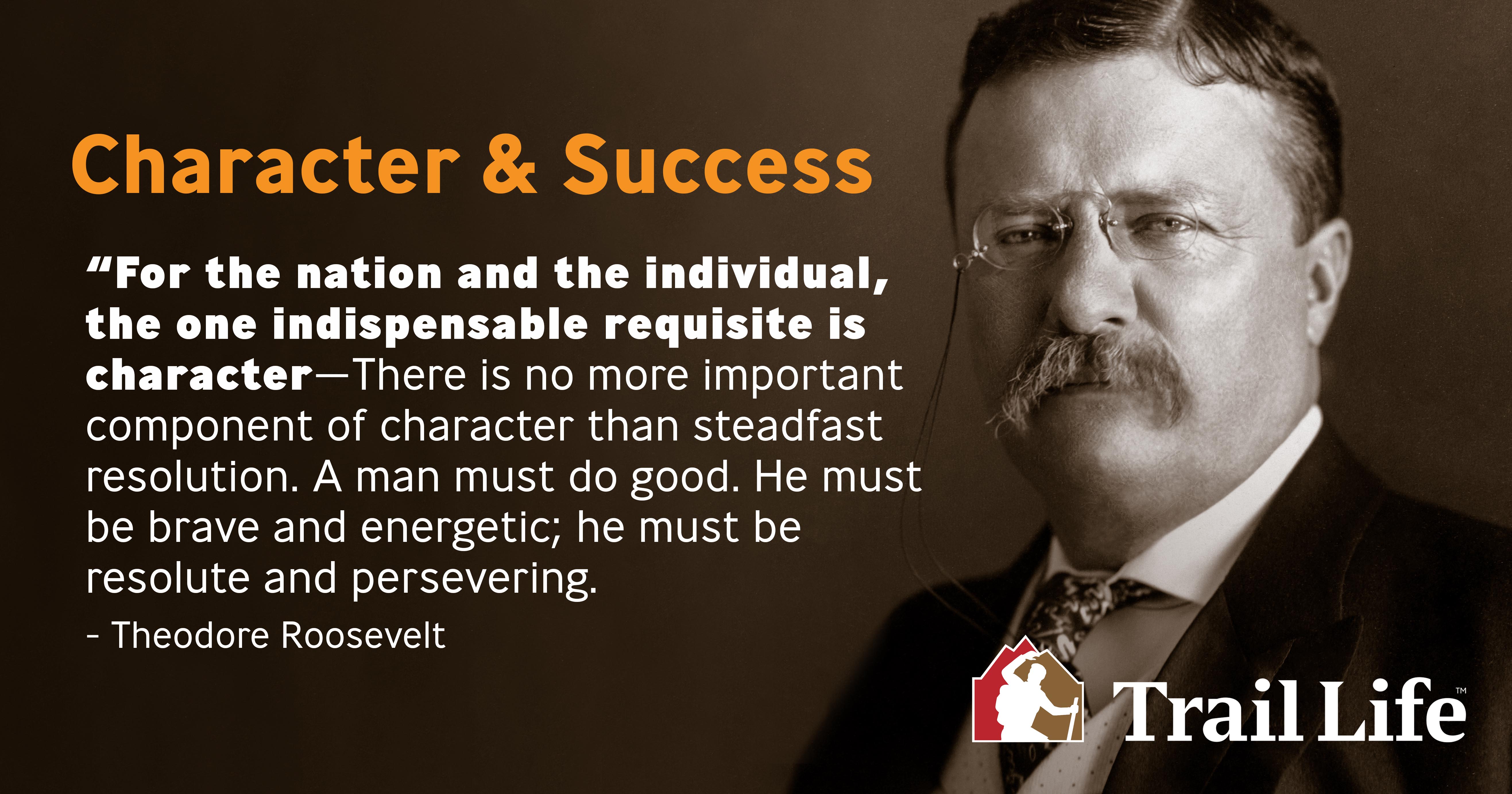

Theodore Roosevelt: Character and Success

Bodily vigor is good, and vigor of intellect is even better, but far above both is character. In the long run, in the great battle of life, no brilliancy of intellect, no perfection of bodily development, will count when weighed in the balance against that assemblage of virtues, active and passive, of moral qualities, which we group together under the name of character. Of course this does not mean that either intellect or bodily vigor can safely be neglected. On the contrary, it means that both should be developed. Character is forged on the anvil of experience.

The very most successful men we have ever had, men like Lincoln, had no chance to go to college, but did have such indomitable tenacity and such keen appreciation of the value of wisdom that they set to work and learned for themselves far more than they could have been taught in any academy. The chances of a man doing good work are immensely increased if he has trained his mind. Of course, if, as a result of his high-school, academy, or college experience, he gets to thinking that the only kind of learning is that to be found in books, he will do very little; but if he keeps his mental balance,—that is, if he shows character,—he will understand both what learning can do and what it cannot, and he will be all the better the more he can get.

A good deal the same thing is true of bodily development. To study hard implies character in the student, and to work hard at a sport which entails severe physical exertion and steady training also implies character. All kinds of qualities go to make up character, for, emphatically, the term should include the positive no less than the negative virtues. If we say of a boy or a man, "He is of good character," we mean that he does not do a great many things that are wrong, and we also mean that he does do a great many things which imply much effort of will and readiness to face what is disagreeable. He must not steal, he must not be intemperate, he must not be vicious in any way; he must not be mean or brutal; he must not bully the weak. In fact, he must refrain from whatever is evil. But besides refraining from evil, he must do good. He must be brave and energetic; he must be resolute and persevering. The Bible always inculcates the need of the positive no less than the negative virtues, although certain people who profess to teach Christianity are apt to dwell wholly on the negative. We are bidden not merely to be harmless as doves, but also as wise as serpents. It is very much easier to carry out the former part of the order than the latter; while, on the other hand, it is of much more importance for the good of mankind that our goodness should be accompanied by wisdom than that we should merely be harmless. If with the serpent wisdom we unite the serpent guile, terrible will be the damage we do; and if, with the best of intentions, we can only manage to deserve the epithet of "harmless," it is hardly worth while to have lived in the world at all.

Perhaps there is no more important component of character than steadfast resolution. The boy who is going to make a great man, or is going to count in any way in after life, must make up his mind not merely to overcome a thousand obstacles, but to win in spite of a thousand repulses or defeats. He may be able to wrest success along the lines on which he originally started. He may have to try something entirely new. On the one hand, he must not be volatile and irresolute, and, on the other hand, he must not fear to try a new line because he has failed in another. Grant did well as a boy and well as a young man; then came a period of trouble and failure, and then the Civil War and his opportunity; and he grasped it, and rose until his name is among the greatest in our history. Young Lincoln, struggling against incalculable odds, worked his way up, trying one thing and another until he, too, struck out boldly into the turbulent torrent of our national life, at a time when only the boldest and wisest could so carry themselves as to win success and honor; and from the struggle he won both death and honor, and stands forevermore among the greatest of mankind.

Character is shown in peace no less than in war. As the greatest fertility of invention, the greatest perfection of armament, will not make soldiers out of cowards, so no mental training and no bodily vigor will make a nation great if it lacks the fundamental principles of honesty and moral cleanliness. After the death of Alexander the Great nearly all of the then civilized world was divided among the Greek monarchies ruled by his companions and their successors. This Greek world was very brilliant and very wealthy. But the heart of the people was incurably false, incurably treacherous and debased. Almost every statesman had his price, almost every soldier was a mercenary who, for a sufficient inducement, would betray any cause. Moral corruption ate into the whole social and domestic fabric, until, a little more than a century after the death of Alexander, the empire which he had left had become a mere glittering shell, which went down like a house of cards on impact with the Romans; for the Romans, with all their faults, were then a thoroughly manly race—a race of strong, virile character.

Alike for the nation and the individual, the one indispensable requisite is character—character that does and dares as well as endures, character that is active in the performance of virtue no less than firm in the refusal to do anything that is vicious or degraded.

Click Here to Read Roosevelt's Entire Essay Character and Success